|

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

Renaissance

Martial Arts Literature

|

|

"Princes

and Lords learn to survive with this art, in earnest and in play. “So

from this art comes all sorts of good, with arms cities are subdued |

|

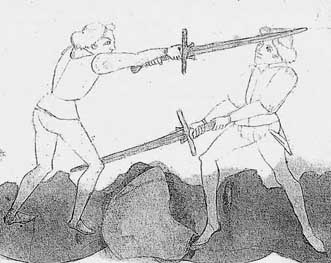

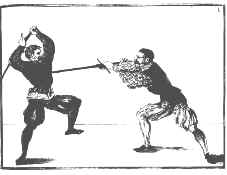

The little known surviving

treatises and guidebooks of fighting skills produced by European

authors are numerous and diverse.

Books and manuscripts on personal combat skills

flourished in the 15th and 16th

centuries. The

oldest known European fighting text is an anonymous German sword and

buckler manual (MS I.33) produced around c. 1295. Its watercolor pages

feature a series of images of a monk and his partner performing various

attacks and counter attacks and has recently come to be more

appreciated as a source for study of historical European martial arts. The writings of the great

Swabian master Johannes Liechtenauer in the 1380s were highly

influential among German masters for the next two centuries. His

teachings, as chronicled by by the priest and master-at-arms, Hanko

Doebringer, were expanded and written on by many others throughout the

1400s and early 1500s including Paulus Kal, Peter Falkner, Hans von

Speyer, Ludwig Von Eyb, Gregor Erhart, Sigmund Schining, Andre

Pauernfeindt, and others. A major one of these commentators was that of

Sigmund Ringeck in the 1450s and Peter Von Danzig in the 1450s. Among

their teachings, these Fechtbuchs (“fight books” or “fencing books”)

present a consistent emphasis on unarmored foot-combat with long-swords

that incorporate grappling techniques.

In

1410 the Bolognese master Fiore dei Liberi produced a systematic work,

Flos Duellatorium in Armis, which represents the major Italian

contribution to 15th century martial arts literature. Three

different editions of Fiore’s work survive and have become major

resources for modern students. The Fechtbuch

of Hans Talhoffer covering among other things, swordplay, judicial

combat, dagger fighting and wrestling was also influential. It was

produced in several versions from the 1440s to 1460s. Other important

fighting texts surviving from the 15th century include

works such as the Codex Wallerstein, the anonymous “Gladiatorie”

and “Goliath” manuscripts, as well as the Solothurner

Fechtbuch. There is also an anonymous 15th century work on the

use of the medieval pole-axe, Le Jeu de la Hache. The

King of Portugal, Dom Duarte,

produced several training texts in the 1420s.

While two obscure 15th century works on swordplay

from England also survive (the MS 3542 and MS 39564 documents).

Fabian von Auerswald also produced a detailed wrestling manuscript

about 1462, of which a well-illustrated later edition still exists.

Fillipo

Vadi in the 1480s produced another major Italian work on fighting

from the period, which was highly influenced by Fiore’s. The

Hispano-Italian knight Pietro Monte produced several tittles on fighting

and combat skills during the 1480s and ‘90s, including the first

published wrestling book. Hans Czynner produced an illustrated

color work of armored combat on the techniques of “half-swording”

and dagger fighting in armor. Hanns Wurm’s colorfully inked

manual, Das Ringersbuch, of c. 1500 features a range of illustrated

wrestling moves and is characteristic of unarmed texts of the period.

Around 1512 the artist Albrecht DŸrer produced a beautifully

and realistically drawn work illustrating sword and wrestling techniques.

Several versions of Jšrg Wilhalm’s work survive

including a large hand-written color 1523 edition featuring an array

of unarmored and armored long sword techniques.

About 1540 Paulus Hector Mair compiled an immense and a well-illustrated

tome on weapon arts including swords, staffs, daggers, and other weapons.

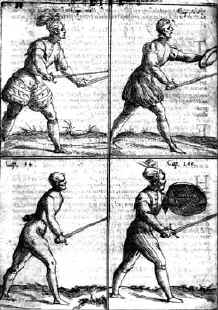

Di

Antonio Manciolino’s work of 1531 is the first known printed

Italian fencing manual. One of the more significant

masters of the 1500s was the Bolognese teacher Achille

Marrozo. His Opera Nova of 1536 is considered the first

text to emphasize the use of the thrust as well as the cut in using

a slender tapering single-hand blade. His work however still covered

the traditional military weapons of the age.

Di

Antonio Manciolino’s work of 1531 is the first known printed

Italian fencing manual. One of the more significant

masters of the 1500s was the Bolognese teacher Achille

Marrozo. His Opera Nova of 1536 is considered the first

text to emphasize the use of the thrust as well as the cut in using

a slender tapering single-hand blade. His work however still covered

the traditional military weapons of the age.

In

1548 the Spanish knight Juan Quixada de Reayo produced a little known

text on mounted combat that reflects traditional 15th century

methods. In 1550 the Florentine

master and contemporary of Marozzo, Francesco Altoni, wrote his own

fencing text that disputed some ideas of Marozzo.

Often attributed to the 1570s, Angelo Viggianni's significant

work of 1551, Lo Schermo, also focused

on the use of a long, slender, tapering single-hand sword.

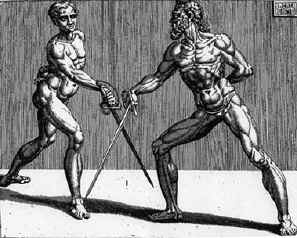

Camillo Agrippa’s treatise on the science of arms

from 1553 was one of the first to focus on use of the thrust

over the cut in civilian swordplay. Considered another one of the

more significant Italian fencing works of the 1500s, Agrippa’s

treatise also represents the transition from military to civilian

swordplay and the use of even more narrow swords.

In

1548 the Spanish knight Juan Quixada de Reayo produced a little known

text on mounted combat that reflects traditional 15th century

methods. In 1550 the Florentine

master and contemporary of Marozzo, Francesco Altoni, wrote his own

fencing text that disputed some ideas of Marozzo.

Often attributed to the 1570s, Angelo Viggianni's significant

work of 1551, Lo Schermo, also focused

on the use of a long, slender, tapering single-hand sword.

Camillo Agrippa’s treatise on the science of arms

from 1553 was one of the first to focus on use of the thrust

over the cut in civilian swordplay. Considered another one of the

more significant Italian fencing works of the 1500s, Agrippa’s

treatise also represents the transition from military to civilian

swordplay and the use of even more narrow swords.

The

Dutch artist Martinus Heemskreck in 1552 illustrated a text, Fechten

& Ringen, with several woodcuts of short sword, two-handed

sword, and wrestling. The

German master Joachim Meyer in 1570 produced a large and extremely

well illustrated training manual that represents one of the high points

of 16th century works. The

work covered a host of assorted swords and weapons and combined some

Italian and German elements. Meyer included material on classroom

play as well as earnest self-defence. Jacob

Sutor later produced a fighting manual in 1612 that was mostly an

updated version of Meyer’s earlier work.

The

Dutch artist Martinus Heemskreck in 1552 illustrated a text, Fechten

& Ringen, with several woodcuts of short sword, two-handed

sword, and wrestling. The

German master Joachim Meyer in 1570 produced a large and extremely

well illustrated training manual that represents one of the high points

of 16th century works. The

work covered a host of assorted swords and weapons and combined some

Italian and German elements. Meyer included material on classroom

play as well as earnest self-defence. Jacob

Sutor later produced a fighting manual in 1612 that was mostly an

updated version of Meyer’s earlier work.

In 1570, Giacomo Di Grassi produced, His True Arte of Defense, a major work on fencing from the period that reveals elements of the changing nature of civilian self-defense concerns and the development of slender duelling swords. An English version was first translated in 1594. The Italian Girolamo Cavalcabo’s work of c.1580, concerned primarily with sword and dagger, was translated into German and French several times over the coming decades. In 1595 Vincentio Saviolo produced, His Practice in Two Books, one of the more influential (and today popular) of late Renaissance manuals. Saviolo’s method reflects the changing form of civilian blade in use. An English version of the text was influential at the time.

Giovanni

Antonio Lovino in 1580 produced a large and elaborate fencing treatise

on rapier as well as other swords and weapons. Until recently, only

limited portions of Lovino’s work were previously known.

Other important Italian fencing works of the late Renaissance

include those by the masters Giovanni Dell’Agochie in 1572,

Camillo Palladini from c. 1580, Alfonso Fallopia in 1584, Nicoletto

Giganti in 1606, Salvator Fabris also in 1606, and later Francesco

Alfieri in 1640. Nearly all these works

reflect the transition from military swords to the civilian duelling

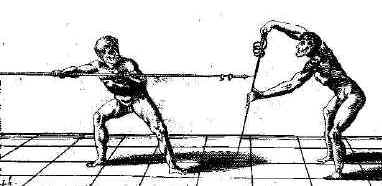

rapiers. In 1610, the Ridolfo Capo Ferro’s,

Gran Simulacro, was first published. Considered

the great Italian master of the rapier and father of modern fencing,

his work codified much of civilian foyning fence for the duel. These

Italian fencing texts offer some of the best of illustrated examples

of rapier fencing.

Giovanni

Antonio Lovino in 1580 produced a large and elaborate fencing treatise

on rapier as well as other swords and weapons. Until recently, only

limited portions of Lovino’s work were previously known.

Other important Italian fencing works of the late Renaissance

include those by the masters Giovanni Dell’Agochie in 1572,

Camillo Palladini from c. 1580, Alfonso Fallopia in 1584, Nicoletto

Giganti in 1606, Salvator Fabris also in 1606, and later Francesco

Alfieri in 1640. Nearly all these works

reflect the transition from military swords to the civilian duelling

rapiers. In 1610, the Ridolfo Capo Ferro’s,

Gran Simulacro, was first published. Considered

the great Italian master of the rapier and father of modern fencing,

his work codified much of civilian foyning fence for the duel. These

Italian fencing texts offer some of the best of illustrated examples

of rapier fencing.

The

master Jeronimo De Carranza wrote his influential tome on Spanish

fencing, De La Philosophia de las Armas,

in 1569. It was to become one of two major Spanish fencing manuals

that formed the heart of the Spanish school for later centuries.

The other great Spanish master of the age was Don Luis P. de

Narvaez, who’s 1599, Libro de las Grandezas de la

Espada (“Book

of the Grandeur of the Sword”) presented rapier material somewhat

different than his master Carranza's. Narvaez’s book is the

other of only two major Spanish fencing manuals from the time. Several

Spanish masters during the 1600s produced fencing books rewriting

the teachings of Carranza or Narvaez and favouring one or the other.

In 1640,

Mendes de Carmona,

a fencing master from Seville,

produced his, Libro de la destreza berdadera

de las armas, an unpublished

manuscript recently discovered.

The

master Jeronimo De Carranza wrote his influential tome on Spanish

fencing, De La Philosophia de las Armas,

in 1569. It was to become one of two major Spanish fencing manuals

that formed the heart of the Spanish school for later centuries.

The other great Spanish master of the age was Don Luis P. de

Narvaez, who’s 1599, Libro de las Grandezas de la

Espada (“Book

of the Grandeur of the Sword”) presented rapier material somewhat

different than his master Carranza's. Narvaez’s book is the

other of only two major Spanish fencing manuals from the time. Several

Spanish masters during the 1600s produced fencing books rewriting

the teachings of Carranza or Narvaez and favouring one or the other.

In 1640,

Mendes de Carmona,

a fencing master from Seville,

produced his, Libro de la destreza berdadera

de las armas, an unpublished

manuscript recently discovered.

The

young Italian soldier and swordsman, Frederico Ghisliero, in 1587

produced an unpublished work, the Regole,

revealing connections to Spanish styles. About 1600 Don Pedro de Heredia

produced his, TraitŽ des Armes,

an illustrated color manuscript on rapier that included grappling

techniques. Heredia was a master-of-arms, cavalry captain and member

of the war council of the king of Spain. His work represents a pragmatic

Spanish style not wrapped in the geometrical ideas of Carranza and

Narvaez. Heredia’s manual is evidence the Spanish school was

neither uniform nor monolithic. Mendes

de Carmona’s, Libro

de la destreza berdadera de las armas, an unpublished manuscript

of 1640 has also recently been rediscovered. Carmona

was a fencing master in Seville, who previously wrote a work on Carranza’s

method. His previously unknown

work is a substantial manuscript covering the principles and fundamentals

of fencing and tactics to use in specific situations. The

most elaborate and lavishly illustrated Renaissance fencing text was

that of Girard Thibault d’Anvers', Academie De L'Espee

(c. 1630), written in French by a Flemish master teaching a version

of the Spanish rapier.

The only truly French

fencing texts known from the Renaissance are that of Henry de Sainct

Didier in 1573, Tracicte’ contenan les ecrets du premier

livre de l’espee seule,

and Francois Dancie wrote his L’espŽe de Combat,

in Tulle, in 1623.

The next known is Charles Besnard’s later, Le

Maitre d’arme Liberal,

of 1653.

The

young Italian soldier and swordsman, Frederico Ghisliero, in 1587

produced an unpublished work, the Regole,

revealing connections to Spanish styles. About 1600 Don Pedro de Heredia

produced his, TraitŽ des Armes,

an illustrated color manuscript on rapier that included grappling

techniques. Heredia was a master-of-arms, cavalry captain and member

of the war council of the king of Spain. His work represents a pragmatic

Spanish style not wrapped in the geometrical ideas of Carranza and

Narvaez. Heredia’s manual is evidence the Spanish school was

neither uniform nor monolithic. Mendes

de Carmona’s, Libro

de la destreza berdadera de las armas, an unpublished manuscript

of 1640 has also recently been rediscovered. Carmona

was a fencing master in Seville, who previously wrote a work on Carranza’s

method. His previously unknown

work is a substantial manuscript covering the principles and fundamentals

of fencing and tactics to use in specific situations. The

most elaborate and lavishly illustrated Renaissance fencing text was

that of Girard Thibault d’Anvers', Academie De L'Espee

(c. 1630), written in French by a Flemish master teaching a version

of the Spanish rapier.

The only truly French

fencing texts known from the Renaissance are that of Henry de Sainct

Didier in 1573, Tracicte’ contenan les ecrets du premier

livre de l’espee seule,

and Francois Dancie wrote his L’espŽe de Combat,

in Tulle, in 1623.

The next known is Charles Besnard’s later, Le

Maitre d’arme Liberal,

of 1653.

The

master George Silver published his Paradoxes of Defense defending

traditional English swordplay in 1599. He wrote his, Brief Instructions

Upon my Paradoxes of Defence, a year later. His work is the

primary source for information on English methods of martial arts

from the Renaissance and is a favorite study source for modern students

of historical fencing. Silver, a critic

of the rapier, pragmatically described the use of short sword or back-sword,

buckler, staff, and dagger. In 1614, George

Hale wrote, The Private Schoole of Defence, commenting on English

fighting schools of the day as well as recommendations on the rapier

method. In 1617 Joseph Swetnam wrote a

rapier and back sword treatise entitled, The Schoole of the Noble

and Worthy Science of Defence and in 1639 one “G. A.”

published a book on swordsmanship, Pallas Armata - The Gentleman's

Armory. It has been suggested that

the author was one, Gideon Ashwell. By 1650 the Marquise of Newcastle

wrote his own short treatise, The Truthe off the Sorde, a little-known

work based on the Spanish School.

The

master George Silver published his Paradoxes of Defense defending

traditional English swordplay in 1599. He wrote his, Brief Instructions

Upon my Paradoxes of Defence, a year later. His work is the

primary source for information on English methods of martial arts

from the Renaissance and is a favorite study source for modern students

of historical fencing. Silver, a critic

of the rapier, pragmatically described the use of short sword or back-sword,

buckler, staff, and dagger. In 1614, George

Hale wrote, The Private Schoole of Defence, commenting on English

fighting schools of the day as well as recommendations on the rapier

method. In 1617 Joseph Swetnam wrote a

rapier and back sword treatise entitled, The Schoole of the Noble

and Worthy Science of Defence and in 1639 one “G. A.”

published a book on swordsmanship, Pallas Armata - The Gentleman's

Armory. It has been suggested that

the author was one, Gideon Ashwell. By 1650 the Marquise of Newcastle

wrote his own short treatise, The Truthe off the Sorde, a little-known

work based on the Spanish School.

This

description of Renaissance martial arts literature is far from complete.

Many other fighting manuals were certainly produced in the 16th

and 17th centuries by a host of other masters and writers.

In 1620 for example, Hans Wilhelm Schšffer fashioned an

enormous work, Fechtkunst, that contained 672 crude rapier

illustrations each one fully described and annotated.

Other German fencing teachers in the early 1600s were

rewriting Italian texts.

This

description of Renaissance martial arts literature is far from complete.

Many other fighting manuals were certainly produced in the 16th

and 17th centuries by a host of other masters and writers.

In 1620 for example, Hans Wilhelm Schšffer fashioned an

enormous work, Fechtkunst, that contained 672 crude rapier

illustrations each one fully described and annotated.

Other German fencing teachers in the early 1600s were

rewriting Italian texts.

The

Dutchman, Johannes Georgius Pascha, in 1657 offered a rapier text

that included substantial material on the pike and unarmed combat.

Fencing works besides those focused on swords or wrestling

were also written during the Renaissance. For example, Andres

Legnitzer wrote on the spear in the early 1400s, while Ott Jud did

the same on wrestling and Hans LeckŸchner also made a treatise

on the Langen Messer (“large-knife”).

In 1603, the Italian, Lelio de Tedeschi,

produced a manual on the art of disarming while in 1616 the Spaniard

Atanasio de Ayala wrote a short text dealing with staff weapons

and Bonaventura Pistofilo’s Il Torneo,

Bologna 1627, was on the use of the polaxe.

Antonio Quintino’s 1613, “Jewels of Wisdom.”

included 16 pages of grappling and wrestling in swordplay as well

as material on animal fighting. Before

1620 Giovan' Battista Gaiani had also written two books on swordsmanship

for horseback.

The

Dutchman, Johannes Georgius Pascha, in 1657 offered a rapier text

that included substantial material on the pike and unarmed combat.

Fencing works besides those focused on swords or wrestling

were also written during the Renaissance. For example, Andres

Legnitzer wrote on the spear in the early 1400s, while Ott Jud did

the same on wrestling and Hans LeckŸchner also made a treatise

on the Langen Messer (“large-knife”).

In 1603, the Italian, Lelio de Tedeschi,

produced a manual on the art of disarming while in 1616 the Spaniard

Atanasio de Ayala wrote a short text dealing with staff weapons

and Bonaventura Pistofilo’s Il Torneo,

Bologna 1627, was on the use of the polaxe.

Antonio Quintino’s 1613, “Jewels of Wisdom.”

included 16 pages of grappling and wrestling in swordplay as well

as material on animal fighting. Before

1620 Giovan' Battista Gaiani had also written two books on swordsmanship

for horseback.

The teachings of these masters

do not appear to reflect a set "style" or a "Way" so much as a

systematic tradition of using proven and efficient techniques within a

sophisticated understanding of general fighting principles. Much of

what we know of these many guidebooks and fighting treatises is

changing and expanding. Although

just beginning, serious modern study and interpretation of Renaissance

martial arts literature is now well underway.

In addition to those described here, many other

martial arts manuals were known to have been produced, but existing

copies have yet to be found. Previously

unexamined collections that have recently become available and should

soon open up will inevitably bring to light even more source manuals. It is an exciting time for

research as the hunt for further Renaissance martial arts literature

continues.

View our original web documentary

series on

the Martial Arts of Renaissance Europe here:

See also Introduction to Historical European Martial Arts

and|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|||