The Sword & Buckler Tradition -

Part 1 The Sword & Buckler Tradition -

Part 1

By J. Clements

Along with the longsword as

a foundational weapon of training, the ARMA has always emphasized

the sword and buckler as a vital tool of study. We now

present here one of the most comprehensive looks at this system

ever offered. The conclusions that can be drawn from the

evidence are somewhat surprising and may lead students of the

subject to reappraise the historical importance of this fencing

method .

As a fencing

tradition in Europe the sword and buckler method was one of

the oldest and most continuous combative systems.[1]

To a large degree however, its place in fencing has been

overshadowed by both the popular image of sword and shield fighting

in the Middle Ages and the later Renaissance idea of rapier

and dagger duelling. But today, modern enthusiasts and

students of historical European martial arts are once again

acquiring respect for this effective weapon combination.

The result is something of a re-evaluation of the familiar conception

of this versatile fighting method.

Although,

the sword and buckler is often associated with the fencing methods

of the early 1500s and with the common serving man, it was a

form of fighting with a much longer tradition. Sword and buckler

fighting also became a “combat sport” of sorts, but

not before it had already long been a martial system of self-defense

and battlefield skill. What is recognizable about the

buckler is that it was foremost a military tool used in war

by both soldiers and knights. That the tradition survived

longer than large shields and ended up occasionally facing off

against the rapier has engendered it (no small thanks to Shakespeare)

with something of an unjust legacy. Given its military

fitness, its eventual unsuitability for civilian duelling and

urban combat during the age of the rapier comes as no surprise. Although,

the sword and buckler is often associated with the fencing methods

of the early 1500s and with the common serving man, it was a

form of fighting with a much longer tradition. Sword and buckler

fighting also became a “combat sport” of sorts, but

not before it had already long been a martial system of self-defense

and battlefield skill. What is recognizable about the

buckler is that it was foremost a military tool used in war

by both soldiers and knights. That the tradition survived

longer than large shields and ended up occasionally facing off

against the rapier has engendered it (no small thanks to Shakespeare)

with something of an unjust legacy. Given its military

fitness, its eventual unsuitability for civilian duelling and

urban combat during the age of the rapier comes as no surprise.

But

the study of the sword and buckler has suffered somewhat from

a lack of attention by historians of fencing and Medieval warfare.

On the one hand, it is so ubiquitous as to not be of much significance,

and on the other, because of comparisons to 16th

century rapier fencing, it is frequently viewed as being somehow

brutish or unsophisticated. Further, while assorted types

of shield developed and changed their shapes and sizes, bucklers

remained much more consistent, so scholars and historians have

not had much reason to focus on them. As well, unlike

shields bucklers served no heraldic function either and this

too has perhaps limited some of their appeal. But

the study of the sword and buckler has suffered somewhat from

a lack of attention by historians of fencing and Medieval warfare.

On the one hand, it is so ubiquitous as to not be of much significance,

and on the other, because of comparisons to 16th

century rapier fencing, it is frequently viewed as being somehow

brutish or unsophisticated. Further, while assorted types

of shield developed and changed their shapes and sizes, bucklers

remained much more consistent, so scholars and historians have

not had much reason to focus on them. As well, unlike

shields bucklers served no heraldic function either and this

too has perhaps limited some of their appeal.

La Petite Defense

A

buckler differs from a shield in that the latter is carried

by straps and worn on the arm whereas the former is held in

single-hand in a “fist” grip. It is difficult

to trace the history of the weapon as many times any type of

round shield or small targe would be called buckler, regardless

of whether it was held in the fist or worn on the arm.[2] The buckler

was a small, maneuverable, hand-held shield for deflecting and

punching blows. It was usually round and made of metal but occasionally

of hardened leather or layers of wood. (Tarassuk & Blaire,

p. 105). Bucklers were typically round and frequently

between 8 to 16 inches in diameter, but octagonal, square, and

trapezoidal versions were also known. A

buckler differs from a shield in that the latter is carried

by straps and worn on the arm whereas the former is held in

single-hand in a “fist” grip. It is difficult

to trace the history of the weapon as many times any type of

round shield or small targe would be called buckler, regardless

of whether it was held in the fist or worn on the arm.[2] The buckler

was a small, maneuverable, hand-held shield for deflecting and

punching blows. It was usually round and made of metal but occasionally

of hardened leather or layers of wood. (Tarassuk & Blaire,

p. 105). Bucklers were typically round and frequently

between 8 to 16 inches in diameter, but octagonal, square, and

trapezoidal versions were also known.

Considerable varieties

of bucklers were developed. Often a pointed spike protruded

from the central boss or umbo.[3]

Many bucklers were pointed with a central tip or several smaller

“teeth”. These points could be used offensively

to great effect as well as aided in binding and deflecting an

opponent’s weapon. John Stow wrote in 1631 how using

the buckler’s long “pyke” (a spikes 8- 12 inches

long) it was the habit of the old fighters “either to breake

the swords of their enemies, or suddenly to runne into them

and stab”. (Aylward, p. 17). An English Royal proclamation in 1562 even complained of “bucklers

with long pykes in them.” (Norman, p. 24) and a

spiked buckler from c. 1607 was even found at the Jamestown

settlement fort in Virginia. Some 16th century

bucklers also had raised metal rings, hooks, or bands that allowed

for the catching or knocking of opposing blades. Samples

of bucklers with these can be seen on display today in the Wallace

Collection Museum in London. Even the special concave

buckler, ostensibly developed in the 1500s to more easily facilitate

deflecting of rapier thrusts, seems to appear much earlier in

a French image of 1375. The light and shadow in the artwork

clearly show the buckler to be curved inward and given the variety

of short, tapering, thrusting swords in use at the time, this

is not difficult to accept. Considerable varieties

of bucklers were developed. Often a pointed spike protruded

from the central boss or umbo.[3]

Many bucklers were pointed with a central tip or several smaller

“teeth”. These points could be used offensively

to great effect as well as aided in binding and deflecting an

opponent’s weapon. John Stow wrote in 1631 how using

the buckler’s long “pyke” (a spikes 8- 12 inches

long) it was the habit of the old fighters “either to breake

the swords of their enemies, or suddenly to runne into them

and stab”. (Aylward, p. 17). An English Royal proclamation in 1562 even complained of “bucklers

with long pykes in them.” (Norman, p. 24) and a

spiked buckler from c. 1607 was even found at the Jamestown

settlement fort in Virginia. Some 16th century

bucklers also had raised metal rings, hooks, or bands that allowed

for the catching or knocking of opposing blades. Samples

of bucklers with these can be seen on display today in the Wallace

Collection Museum in London. Even the special concave

buckler, ostensibly developed in the 1500s to more easily facilitate

deflecting of rapier thrusts, seems to appear much earlier in

a French image of 1375. The light and shadow in the artwork

clearly show the buckler to be curved inward and given the variety

of short, tapering, thrusting swords in use at the time, this

is not difficult to accept.

The

versatility of the sword and buckler as a method of fighting

can be said to lay in its simplicity. As a two-weapon combination,

it is simultaneously defensive and offensive. It offered

some protection against missile weapons and was convenient for

facing heavier weapons such as polearms and axes.[4]

Yet, its small size made it agile and quick. Combined

with a good shearing sword or tapering cut-and-thrust blade,

it could deflect attacks, strike blows of its own, and yet still

allow the user’s own sword to cut around in any direction.

Another advantage of metal bucklers was that unlike wooden

shields, the point of an opponent’s weapon would not get

stuck in the face of the buckler nor would the edge of a blade

damage the rim (although, when this occurred it could be used

to the shield man’s advantage). In many of the historical

images of sword and buckler combat the familiar fighting postures

found in longsword fencing manuals can be easily discerned,

such as the wards of: high, middle, low, back, and hanging. The

versatility of the sword and buckler as a method of fighting

can be said to lay in its simplicity. As a two-weapon combination,

it is simultaneously defensive and offensive. It offered

some protection against missile weapons and was convenient for

facing heavier weapons such as polearms and axes.[4]

Yet, its small size made it agile and quick. Combined

with a good shearing sword or tapering cut-and-thrust blade,

it could deflect attacks, strike blows of its own, and yet still

allow the user’s own sword to cut around in any direction.

Another advantage of metal bucklers was that unlike wooden

shields, the point of an opponent’s weapon would not get

stuck in the face of the buckler nor would the edge of a blade

damage the rim (although, when this occurred it could be used

to the shield man’s advantage). In many of the historical

images of sword and buckler combat the familiar fighting postures

found in longsword fencing manuals can be easily discerned,

such as the wards of: high, middle, low, back, and hanging.

A Lengthy Legacy

In the Middle Ages,

bucklers were common armaments among both knights and common

soldiers – even more so than shields. A buckler

was less cumbersome and more agile than a larger shield and

easier to carry about or wear on the hip. We know that

sword and buckler play was a popular pastime in northern Italy,

in Germany, and in England. As

British historical fencing researcher-practitioner Martin J.

Austwick has pointed out: “The earliest references to professional

combat instructors or masters of defense as they were to become

known all have one thing in common. They refer to schools

of sword and buckler. Add to this the fact that the earliest

known fechtbuch or fight book is dedicated solely to sword and

buckler combat, then it becomes apparent that sword and buckler

combat is arguably the oldest surviving martial tradition within

Western Martial Arts today.”[5] In the Middle Ages,

bucklers were common armaments among both knights and common

soldiers – even more so than shields. A buckler

was less cumbersome and more agile than a larger shield and

easier to carry about or wear on the hip. We know that

sword and buckler play was a popular pastime in northern Italy,

in Germany, and in England. As

British historical fencing researcher-practitioner Martin J.

Austwick has pointed out: “The earliest references to professional

combat instructors or masters of defense as they were to become

known all have one thing in common. They refer to schools

of sword and buckler. Add to this the fact that the earliest

known fechtbuch or fight book is dedicated solely to sword and

buckler combat, then it becomes apparent that sword and buckler

combat is arguably the oldest surviving martial tradition within

Western Martial Arts today.”[5]

The

primary use of the buckler in Europe was by infantry. Light

infantry, made up of commoners armed with bucklers and swords

or falchions lined up behind troops with pole-weapons, were

used frequently in armies during the 1100s to 1300s. Early Medieval

pictorial sources, from c.650 to c.1100, additionally show bucklers

in use by Celtic, Frankish, and Byzantine horsemen. Medievalist

Donald Kagay reports of ordinances from 1363 by the Crown of

Aragon’s parliament of Monzón which specified the military

equipment required for frontier troops on active duty.

Light mounted troops were required to have among their weapons

a cuyrase (breast plate), a camisol (maile shirt),

helmet, lance, and a small round leather shield called a darga

de scut.[6]

Bucklers are also common in Medieval artwork depicting Middle

Eastern warriors, but these small shields are actually for mounted

combat and are typically held sideways by two straps as opposed

to the center-held buckler with its single handle. But

the sword and buckler was most effective in foot combat such

as with the Italian Rotulari (c. 1475) buckler infantry.

One historian best explains their development: “It was

to combat the new emphasis on field fortifications that a new

type of infantry became popular in Italian armies. This was

the so-called ‘sword and buckler’ infantry, first

experimented with by Braccio. They were lightly armed, agile,

and equipped for hand-to-hand offensive fighting. The type had

already been developed in Spain in fighting with the Moors,

and the establishment of Aragonese in Naples in the 1440s clearly

had something to do with their appearance in Italy at this time.”[7] The

primary use of the buckler in Europe was by infantry. Light

infantry, made up of commoners armed with bucklers and swords

or falchions lined up behind troops with pole-weapons, were

used frequently in armies during the 1100s to 1300s. Early Medieval

pictorial sources, from c.650 to c.1100, additionally show bucklers

in use by Celtic, Frankish, and Byzantine horsemen. Medievalist

Donald Kagay reports of ordinances from 1363 by the Crown of

Aragon’s parliament of Monzón which specified the military

equipment required for frontier troops on active duty.

Light mounted troops were required to have among their weapons

a cuyrase (breast plate), a camisol (maile shirt),

helmet, lance, and a small round leather shield called a darga

de scut.[6]

Bucklers are also common in Medieval artwork depicting Middle

Eastern warriors, but these small shields are actually for mounted

combat and are typically held sideways by two straps as opposed

to the center-held buckler with its single handle. But

the sword and buckler was most effective in foot combat such

as with the Italian Rotulari (c. 1475) buckler infantry.

One historian best explains their development: “It was

to combat the new emphasis on field fortifications that a new

type of infantry became popular in Italian armies. This was

the so-called ‘sword and buckler’ infantry, first

experimented with by Braccio. They were lightly armed, agile,

and equipped for hand-to-hand offensive fighting. The type had

already been developed in Spain in fighting with the Moors,

and the establishment of Aragonese in Naples in the 1440s clearly

had something to do with their appearance in Italy at this time.”[7]

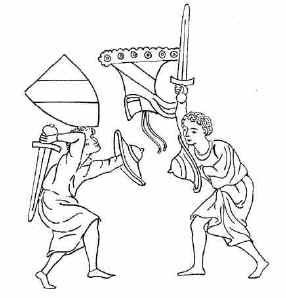

| There is no question of the buckler's popularity over

the centuries. The Holkham Picture Bible Book

from the early 1300s offers illustrations of combat

including that between mounted knights using sword and

lance, and between common soldiers (le commoune gent)

on foot using axe, falchion, spear, and short sword

with small round buckler. (Prestwich, p.

115). An image, dated to the 2nd half of the 14th century,

of sword and buckler facing longsword, can even be found

in the chapter on violent crimes from the State laws

of King Magnus Eriksson, Sweden. |

|

| |

|

|

|

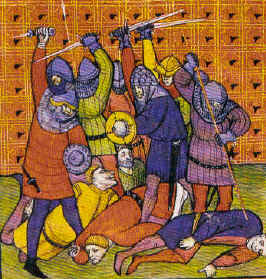

Fresco paintings from c.1340 of northern Italian infantry

fighting with sword and buckler can be found on the

castle of Sabbionara at Avio in Trento. A late 13th

century image from Tuscany also depicts maile-clad helmeted

infantry armed only with sword and buckler. A

French illumination from c.1317 of the Legende de St.

Denis shows militia meeting the king and equipped with

buckler among other weapons (MS Fr. 2090-2. f.129r.

Paris). A carved relief depicting two sleeping

Swabian guards from c.1350 shows them equipped with

sword and buckler and wearing maile and partial plate

armor. (Nicolle, Arms and Armor, p. 191).

An astrological text from the late 14th century offers

a colorful image depicting a range of martial exercises

practiced in the sun outdoors, including sword and buckler

fencing. (C. F. Black, p. 132) |

| Another manuscript illustration of a boar hunt dated

c.1300-1350 shows two hunters armed with sword and buckler

and sword and cloak. (Nicolle, Arms and Armor,

p. 191).[8] A c.1305 image

from Flanders of the battle Courtrai portrays numerous

maile-clad helmeted Flemish militiamen on foot with

bucklers, but no larger shields are shown. |

|

At

the Agincourt battle in 1415, the only defence recorded for

the English bowmen is a round buckler 1 foot in diameter.

(Edge, p. 65). The 1457, Bridport Muster Roll shows

that many of the common folk called up (including 5 apparent

women) were equipped with sword and buckler. While a description

by Dominic Mancini in 1483 of the equipment of the troops under

Richard Duke of Gloucester (the future Richard III) noted, “the

sword is accompanied by an iron buckler.” (Edge, p. 128).

The Spanish sword and buckler men of the early 1500s are

among the best known proponents of the weapons. They wreaked

havoc up and down the battlefields of Europe, even against the

famed Swiss pikemen. A favored tactic was to close against

pike formations and try to roll under the polearms then pop

up among their clustered opponents where their shorter weapons

could wreak havoc. At

the Agincourt battle in 1415, the only defence recorded for

the English bowmen is a round buckler 1 foot in diameter.

(Edge, p. 65). The 1457, Bridport Muster Roll shows

that many of the common folk called up (including 5 apparent

women) were equipped with sword and buckler. While a description

by Dominic Mancini in 1483 of the equipment of the troops under

Richard Duke of Gloucester (the future Richard III) noted, “the

sword is accompanied by an iron buckler.” (Edge, p. 128).

The Spanish sword and buckler men of the early 1500s are

among the best known proponents of the weapons. They wreaked

havoc up and down the battlefields of Europe, even against the

famed Swiss pikemen. A favored tactic was to close against

pike formations and try to roll under the polearms then pop

up among their clustered opponents where their shorter weapons

could wreak havoc.

By 1500, the Spanish

infantry of Gonsalvo de Cordova used short thrusting swords

and bucklers, wore steel caps, breast and back plates, and greaves.

(Oman, p. 63). The infamous Machiavelli himself in his

own 1521 Arte of Warre, wrote of how at the battle of

Barletta in 1503 the Spanish sword and buckler men dealt with

the Swiss pikemen: “When they came to engage, the Swiss

pressed so hard on their enemy with their pikes, that they soon

opened their ranks; but the Spaniards, under the cover of their

bucklers, nimbly rushed in upon them with their swords, and

laid about them so furiously, that they made a very great slaughter

of the Swiss, and gained a complete victory.” (Machiavelli,

p. 66). As Machiavelli tells it, the Spaniards at the battle

of Ravenna in 1512 fell furiously on the Germans, “rushing

at the pikes, or throwing themselves on the ground and slipping

below the points, so that they darted in among the legs of the

pikemen.” The Spaniards “made so good a use

of their swords, that not one of the enemy would have been left

alive, if a body of French cavalry had not fortunately come

up to rescue them.” (Machiavelli, p. 70). “This

fight was typical of many more in which during the first quarter

of the sixteenth century the sword and buckler were proved to

be more than master of the pike.” (Oman, p. 110). In

1618 Adam van Breen wrote a work in the Netherlands on military

drill which in 1625 was reprinted as Mars His Field,

“or The Exercise of Armes, wherein in lively figures is

shewn the Right use and perfect manner of Handling the Buckler,

Sword, and Pike...” By 1500, the Spanish

infantry of Gonsalvo de Cordova used short thrusting swords

and bucklers, wore steel caps, breast and back plates, and greaves.

(Oman, p. 63). The infamous Machiavelli himself in his

own 1521 Arte of Warre, wrote of how at the battle of

Barletta in 1503 the Spanish sword and buckler men dealt with

the Swiss pikemen: “When they came to engage, the Swiss

pressed so hard on their enemy with their pikes, that they soon

opened their ranks; but the Spaniards, under the cover of their

bucklers, nimbly rushed in upon them with their swords, and

laid about them so furiously, that they made a very great slaughter

of the Swiss, and gained a complete victory.” (Machiavelli,

p. 66). As Machiavelli tells it, the Spaniards at the battle

of Ravenna in 1512 fell furiously on the Germans, “rushing

at the pikes, or throwing themselves on the ground and slipping

below the points, so that they darted in among the legs of the

pikemen.” The Spaniards “made so good a use

of their swords, that not one of the enemy would have been left

alive, if a body of French cavalry had not fortunately come

up to rescue them.” (Machiavelli, p. 70). “This

fight was typical of many more in which during the first quarter

of the sixteenth century the sword and buckler were proved to

be more than master of the pike.” (Oman, p. 110). In

1618 Adam van Breen wrote a work in the Netherlands on military

drill which in 1625 was reprinted as Mars His Field,

“or The Exercise of Armes, wherein in lively figures is

shewn the Right use and perfect manner of Handling the Buckler,

Sword, and Pike...”

Author

Wilbur Prescott writing on the art of war in late Medieval

Spain, suggests the reason for the proficiency of the Spanish

sword and buckler men of the early 1500s, was curiously,

their considerable experience in late 15th century

siege warfare which at the time relied heavily on close

combat skills with shields. (Prescott, p. 26). Following

along the work of Vegetius (influential throughout the Middle

Ages and Renaissance), Machiavelli even suggested that armies

of the time should actually equip their soldiers with swords

and bucklers. Their advantage in pike warfare lay

in the well-timed ability of such agile fighters to close

in among the longer weapons of their tightly packed adversaries. In

1583 the Italian military writer Cesare d’Evoli said

he favored small round metal shields for deflecting pikes.

(Anglo, p. 220). Author

Wilbur Prescott writing on the art of war in late Medieval

Spain, suggests the reason for the proficiency of the Spanish

sword and buckler men of the early 1500s, was curiously,

their considerable experience in late 15th century

siege warfare which at the time relied heavily on close

combat skills with shields. (Prescott, p. 26). Following

along the work of Vegetius (influential throughout the Middle

Ages and Renaissance), Machiavelli even suggested that armies

of the time should actually equip their soldiers with swords

and bucklers. Their advantage in pike warfare lay

in the well-timed ability of such agile fighters to close

in among the longer weapons of their tightly packed adversaries. In

1583 the Italian military writer Cesare d’Evoli said

he favored small round metal shields for deflecting pikes.

(Anglo, p. 220). |

GO

TO NEXT SECTION

Footnotes for Part

1

[1]

The word is derived from the Old French bocle

for the “buckle-like” boss or umbo on a shield.

The term “boss” is from the 12th century

French Boce, bocle, called bloca, in

12th-13th century Spain (Nicolle,

Arms and Armor, p. 549).

[2]

The 1611 edition of Florio’s Italian-English

dictionary, gives Brocchiéro, Broccoliéro, as “a

buckler, a target, a shield.” Although often

described as near synonymous with the buckler, a targe (or

targa and adarga) differed from a buckler

in that it was a small wooden shield with a leather cover

and leather or metal trim. Some were also covered

with metal studs or spikes. Unlike bucklers, targes

were worn on the arm like other types of shields.

They were also usually flat rather than convex. Elizabethans

referred to the practice of “Sworde

and targat”. The word “targe” apparently

comes from small “targets” placed on archery practice

dummies. Some forms of medium sized steel shields

from the Renaissance are often classed as targes or the

Italian rondella . Though associated with the Scots, the

“targe” was actually used throughout Europe. They

were most popular in the early Renaissance and the Scots

were merely the last to use them.

[3]

Following Livy, T. Thomas’s 1587 Latin-English

dictionary, Dictionarium Linguae Latinae et Anglicanae,

defined umbo as “the bosse of a buckler or shield (London,

R. Boyle). Thomas also listed Parmularius as

“A buckler or target maker, or he that useth such a

one” and the old Roman Pelta as “A target

or buckler like a halfe moone: also a square buckler or

targen.”

[4]

It has also been speculated that an advantage

of the buckler in the crush of Medieval combat lay in its

adaptability. Whereas a larger shield worn on the

arm could be hooked or pulled by various types of polearms

and axes, thereby vulnerably encumbering the fighter, a

smaller more nimble hand-held buckler could easily dislodge

itself from such attempts or suddenly be discarded by a

fighter.

[7]

Michael Mallet.

Mercenaries and Their Masters – Warfare in Renaissance

Italy. Rowman and Littlefield, Totowa, NJ, 1974, p.

155.

- [9] De Wapen-handelinge

van schilt, spies, rapiers, en targis. Nae de nieuwe ordere,

vanden...prince van Oraignien, Mauritius van Nassauw ...

Door Adam van Breen in figuren ... The Hague, Ghedruckt ...door H. Hondius, 1640.

|